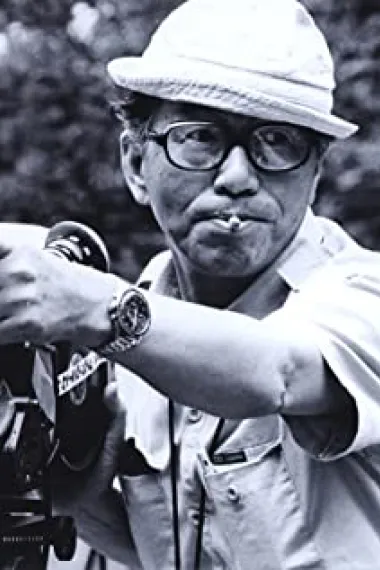

市川昆 (1915) Kon Ichikawa

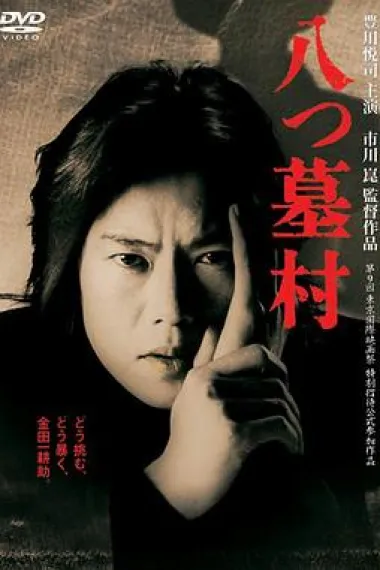

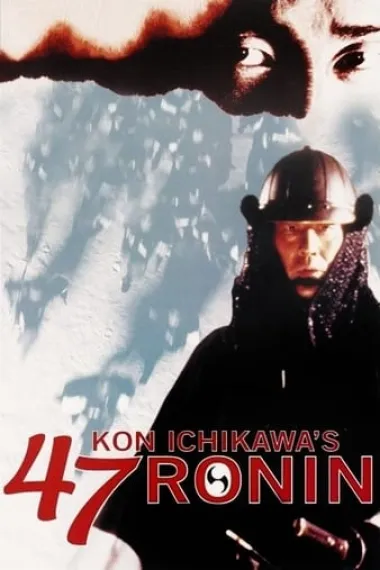

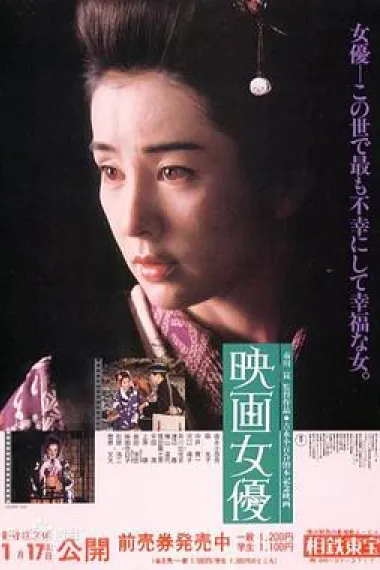

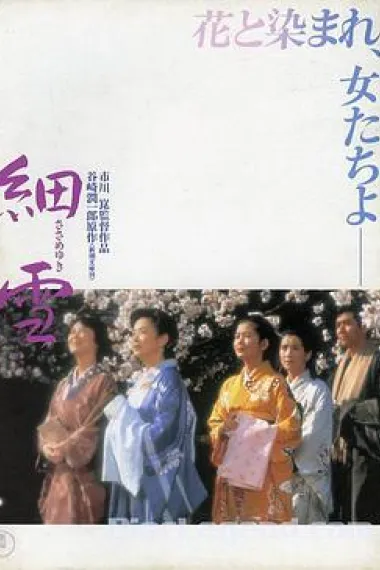

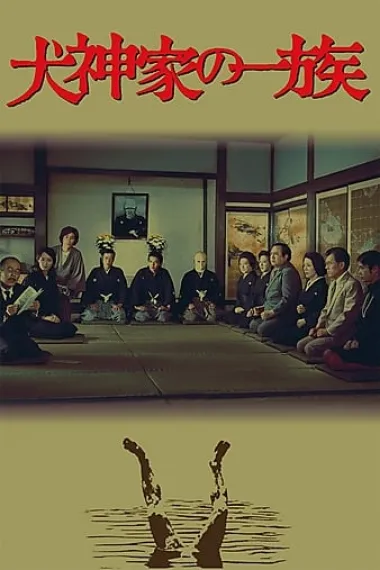

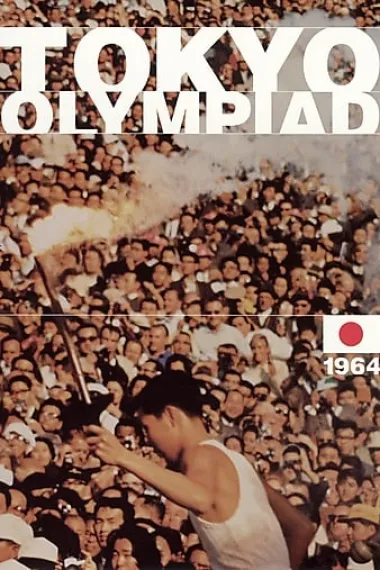

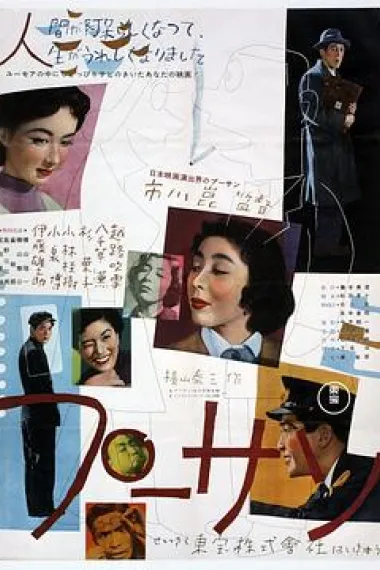

市川崑曾受到沃尔特·迪士尼与让·雷诺阿等风格迥异的艺术家的影响,其作品情感跨度极大——从诙谐幽默到极致讽刺,甚至不乏荒诞诡谲。他早年以漫画家身份开启职业生涯,这种经历深刻体现在其作品中:无论是对宽银幕的精妙运用,还是诸多构图里鲜明而棱角分明的视觉图案,皆可见漫画影响的痕迹。1953年,他执导了改编自横山隆一漫画《普先生》的流行电影《普先生》。在其艺术生涯的不同阶段,市川崑始终证明着自己既能赢得大众喜爱,又从未牺牲艺术追求。作为一位卓越的视觉风格大师与完美主义者,市川崑尤其擅长文学经典的银幕改编,代表作包括夏目漱石的《心》(1955)、三岛由纪夫的《炎上》(1958)、谷崎润一郎的《键》(1959)与《我是猫》(1975),以及岛崎藤村的《破戒》(1962)。他还致力于经典电影的重拍,如将阿部丰的《足触女人》(1926)改编为1952年版,将衣笠贞之助的《雪之丞变化:第一篇》(1935)改编为1963年版,并将故事背景移植到当代语境。西方世界初识市川崑,始于其作品《缅甸的竖琴》(1956)在1956年威尼斯电影节荣获圣乔治奖。他的史诗级纪录片《东京奥林匹克》(1965,次年上映)与《太平洋独行》(1963)以庄重的视角与丰富的想象力,探索了人类忍耐力的极限。在惊悚片领域,他也贡献了《穴》(1957)、《犬神家族》(1976)及《狱门岛》(1977)等作品。市川崑擅长刻画棱角分明、层次复杂的角色:比如渴望守护金阁寺“纯粹”性而口吃的年轻僧侣(《炎上》);为维持性活力而依赖注射与窥淫癖的老人(《键》);试图隐瞒身份、在正常社会中“伪装”生存的贱民阶层成员(《破戒》)。在近作《映画女优》(1987)中,他致敬了特立独行的日本女演员田中绢代——她曾主演多部沟口健二电影,晚年亦转型为导演。轻松的一面同样存在于市川崑的作品中:其角色包括一只19世纪的猫、一位善良而倒霉的教师,以及以婴儿视角叙述世界的叙事者。他尤其擅长在同一故事中巧妙融合喜剧与悲剧元素。直至1965年,他的妻子、编剧和田夏十始终是其紧密的创作伙伴,两人共同完成了市川崑大多数杰出作品。